The Data Iceberg

Data is primarily harnessed today for commercial and political purposes (think about the Cambridge Analytica scandal for instance).

Much like how you assemble your own IKEA shelves, you’re also a co-creator of the digital services you use. IKEA can sell their shelves at a low cost because you do the assembly yourself. Essentially, you provide free labour. Similarly, in the digital economy, you’re contributing free labour by generating data for commercial operators.

Many digital tools, like search engines, social media platforms, online communities and maps, are often free of charge. This is typically because they can monetize the data you provide to them.

This data is used to gain insights, improve the service, and create new products that investors, partners, customers, advertisers, and others are willing to pay for.

You might have heard the saying: “If you’re not paying for it, you , you are the product.” In many contexts, having digital information about customers combined with a solid business model is as valuable as gold.

We’ll explore this in more depth shortly. But first, let’s delve into how it can be that all this data is invisible to us, when we’re practically swimming in it.

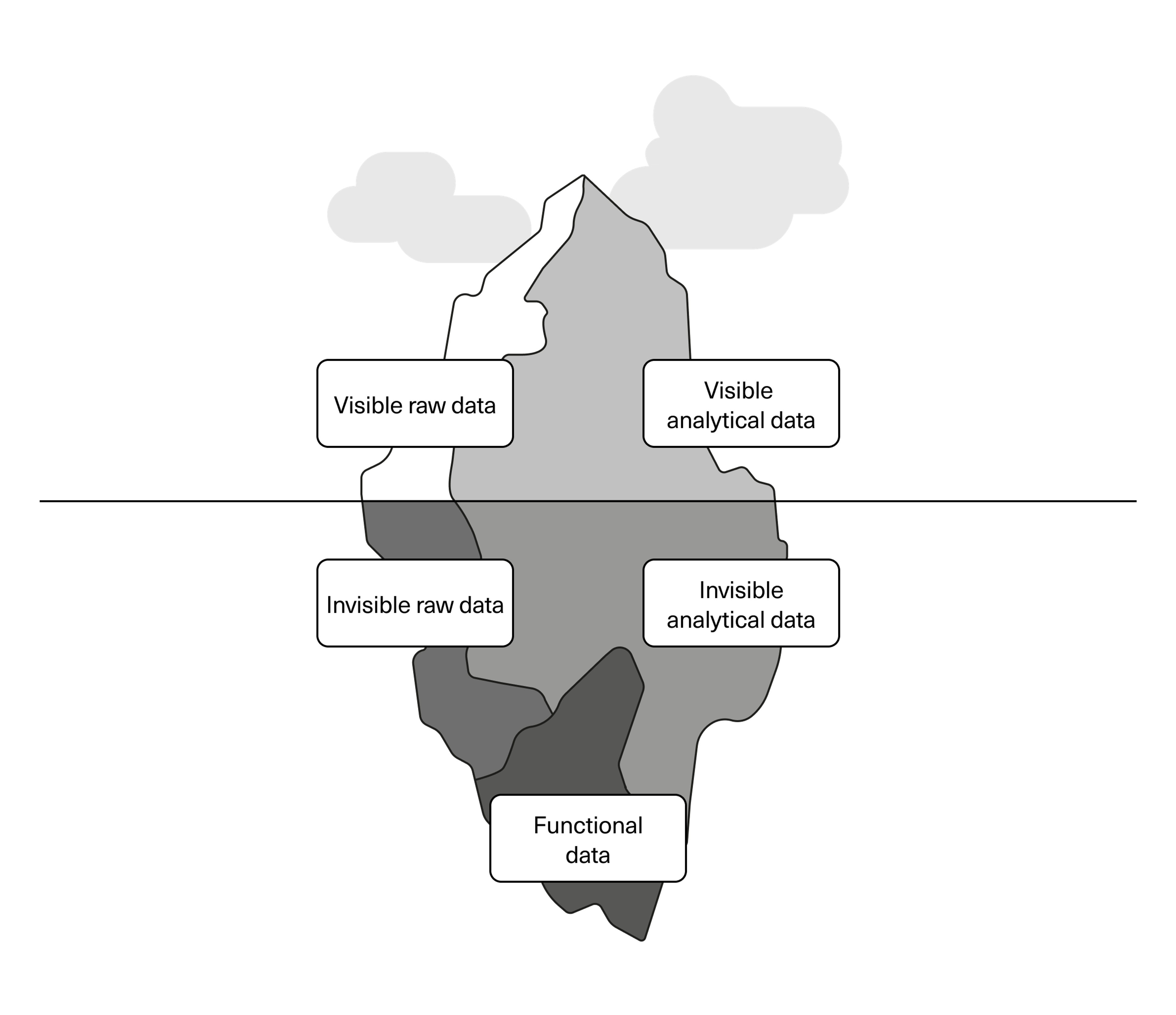

The iceberg model

It can be hard to understand or visualise all of the data that is generated when we interact with digital technology. The iceberg model can make it easier to understand.

As we go about our activities, we leave behind a lot of data, usually without us noticing. We only see the tip of this data iceberg. Like an actual iceberg, most of it is hidden underneath the surface.

The iceberg model is originally a communication model used by Sigmund Freud. It describes how communication between people is actually much more complicated than one would think. On the surface, we have factual aspects, like the words we say. But much of what is actually communicated is hidden beneath the surface, as one has to consider for example the context, our feelings, and complex psychological processes that we’re not consciously aware of.

This model can also be used as a metaphor to describe the interaction between humans and machines, which is also far more complex than we might realise.

We can distinguish between data in three categories: raw data, analytical data, and functional data.

Raw data and analytical data can be both visible and invisible, as you see in the figure, while functional data lies beneath the surface. Let’s take a closer look at what each of these entail.

Raw data

By raw data, we simply mean data that has not (yet) been processed for any specific purpose. Put simply, this is data that has only gone through the first part of the life cycle we discussed in the previous section; it is stored, but not processed for further analysis.

Consider all the data that is visible to us and that we believe we have control over when we interact with digital devices. This could be a tweet, an email, a blog post, a snap you send to a friend, a message on a messaging platform, or a YouTube video. All these are examples of raw data.

These examples also all fall into the category called content data. Content data is information and communication content that we exchange with other people through the use of machines, applications, and platforms. This data is often multimedial, including sound, text, images, videos, and so on.

Another type of raw data is sensor data, such as data about your heart rate and your movements recorded by a smartwatch.

Metadata also emerges from all these interactions. In this context, metadata refers to the descriptive data generated when we interact with digital devices. Beyond the actual content of the tweet or email (content data), there will be metadata about for example the time you sent the tweet, your location, the number of characters, and what browser and device is used.

Some metadata is visible to us, while some remains hidden. It’s mainly this metadata that is used in further analysis processes. This leads us to the next category.

Analytical data

When you watch Netflix, there is obviously content data—the series or film itself. It is just as obvious that Netflix knows what you’re watching.

Beyond this, there’s also a lot of other data being sent to Netflix: where and when you watch, the device you use, video quality, the speed of the network, and so on. They also capture where you pause or stop, where you rewind and watch something again, which genres you prefer, when during the day you watch a film, and much, much more. This data is used to create a profile that might reveal a lot about your habits, mental states, and routines.

These metadata and log files are automatically created when we interact with digital devices, including when our devices interact with each other, like your robot vacuum, e-reader, or smart TV. These log files contain information of how the device is used or behaves and can be utilised for analysis or diagnostics purposes.

Some metadata is visible and shared with us. For example, when you send an email, it might state “sent from my Huawei” or “sent from iPhone” at the bottom. This is metadata and can provide useful information. For instance, an iPhone is generally more expensive than a Huawei, so it can say something about you. Details like when the email was sent, your location, and which email client you used can also be compiled for further analysis.

However, it’s not only log files and metadata that can be analysed. Raw data or content data can also be examined. For example, if you email a company’s customer service, they might use AI technology to analyse the tone of your email to determine if it’s positive or negative, a process known as sentiment analysis or opinion mining.

Functional data

At the bottom of the iceberg, we find functional data. This is the data needed for machines to communicate with each other and for applications and software to operate properly.

What we’re referring to here is data that’s exchanged through certain protocols, such as to identify a user on a website. Protocols, which you’ll learn more about later, provide the framework for information exchange to occur.

This type of data is primarily involved in machine-to-machine communication. However, that doesn’t mean it can’t be useful or interesting to humans. For instance, law enforcement or security agencies might be interested in functional data from a mobile phone that shares information about its location or the network it’s connected to.

You can see these different layers of data in action when a website asks you to accept cookies. If you select “only necessary cookies”, the site won’t collect analytical data about you. However, you can’t decline functional data because without it, the website simply wouldn’t function.

Insight

What does this mean for you and me?

We began by pointing out that we’re both creators and consumers of data—providing the pieces in the digital economy jigsaw puzzle. The iceberg model explains this situation from a practical, non-technical viewpoint. It aims to demystify how data collection works and shed light on processes often invisible to most people.

Sharing some data can be beneficial; it promotes progress and benefits society as a whole. It allows for more efficient communication, more automation, and supports our jobs and societal functions. Services like healthcare platforms and student loans have also become much more efficient.

However, there are concerns with these processes taking place out of sight. From a privacy perspective, it’s problematic not knowing what data you’re sharing; unidentified data that you’re not informed about, or data that is being processed and used by someone else. Even if our data is supposed to be anonymised, we can often be identified under certain conditions. A simple example: If an app shows a series of bicycle rides that all start at the same address, it doesn’t take much imagination or skill to figure out who the rider is. Such workout maps have actually been used to reveal secret military bases!

When you don’t know who has access to your data, you become vulnerable in a new way. We are protected to a certain extent by laws and regulations, but the development happens so fast that even experts have a hard time seeing what it is possible to do with the data we leave behind. You can do certain things to hide yourself, such as using a VPN, or turning off location data on your phone. But becoming entirely anonymous is practically impossible unless you’re ready to live in a forest and survive on hunting and fishing.

As long as you live normally and participate in society, you will leave a digital shadow. We’ll look further into this in the next topic.