What is Data?

Old parish registers, trade registers, telephone directories and music cassettes contain loads of data. So, data is nothing new. It existed long before we had computers and digital data.

However, it’s clear that something new is happening now. To understand what, we need to become more familiar with what data really is.

Definitions

What is data?

There are many definitions of data, which are suitable in different contexts. The word itself is originally the plural of the Latin datum, which means “that which is given”. Today, we mostly use it in the sense of “value”, “information” or “raw information” (meaning not processed).

To lean on the definition in the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia, data is simply information or values that exist in some specific format. They can thus be stored, transferred and processed according to specific rules—so that it becomes understandable and usable for a recipient. In order to be analysed and applied, the data must therefore exist in a data format that is readable and understandable to humans and/or machines.

Data can be analogue or digital. We’ll return to the technical difference between these in the next chapter. The simple explanation, however, is that digital data is data that can be read and used by computers.

What does data look like?

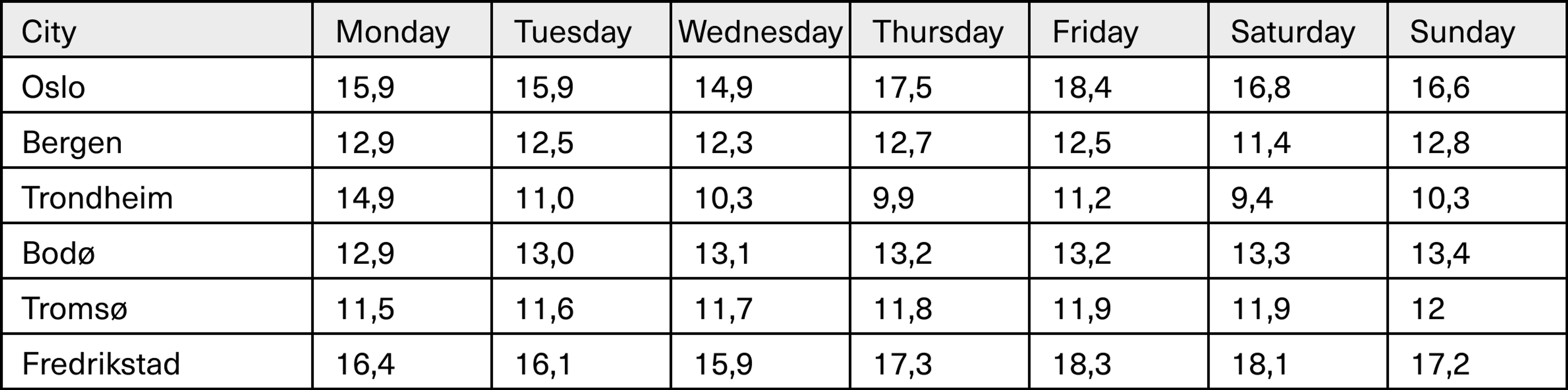

Imagine an Excel sheet with a table showing row upon row of numbers, representing temperatures in a certain place from day to day.

From this, a proficient Excel user could press a few buttons and conjure up a graph visualising the temperature in that place. Such tables and visualisations are what many typically associate with data.

This is correct, but data is also much more than just numbers and tables. There are many non-numeric forms of data—such as observations, photographs, letters, symbols, images, sound, electromagnetic waves and so on.

Data is not always neatly and prettily sorted as in our imagined Excel sheet. Here we have structured data (this applies to things like lists and tables, parish registers and trade registers), but data can also be unstructured (for example, text documents, images and music). And they can exist in a variety of formats.

Even though you hear phrases like “raw information”, it’s important to underline that data is never really “raw” or “neutral”. We abstract reality with data: We use it to create representative categories and measurements of the world around us and ourselves. How this representation turns out is always influenced by who collects the data, and how the data is collected, analysed and put to use.

Data must also be placed in context, and then interpreted and tested, before it can be called information or knowledge.

Data vs. information vs. knowledge

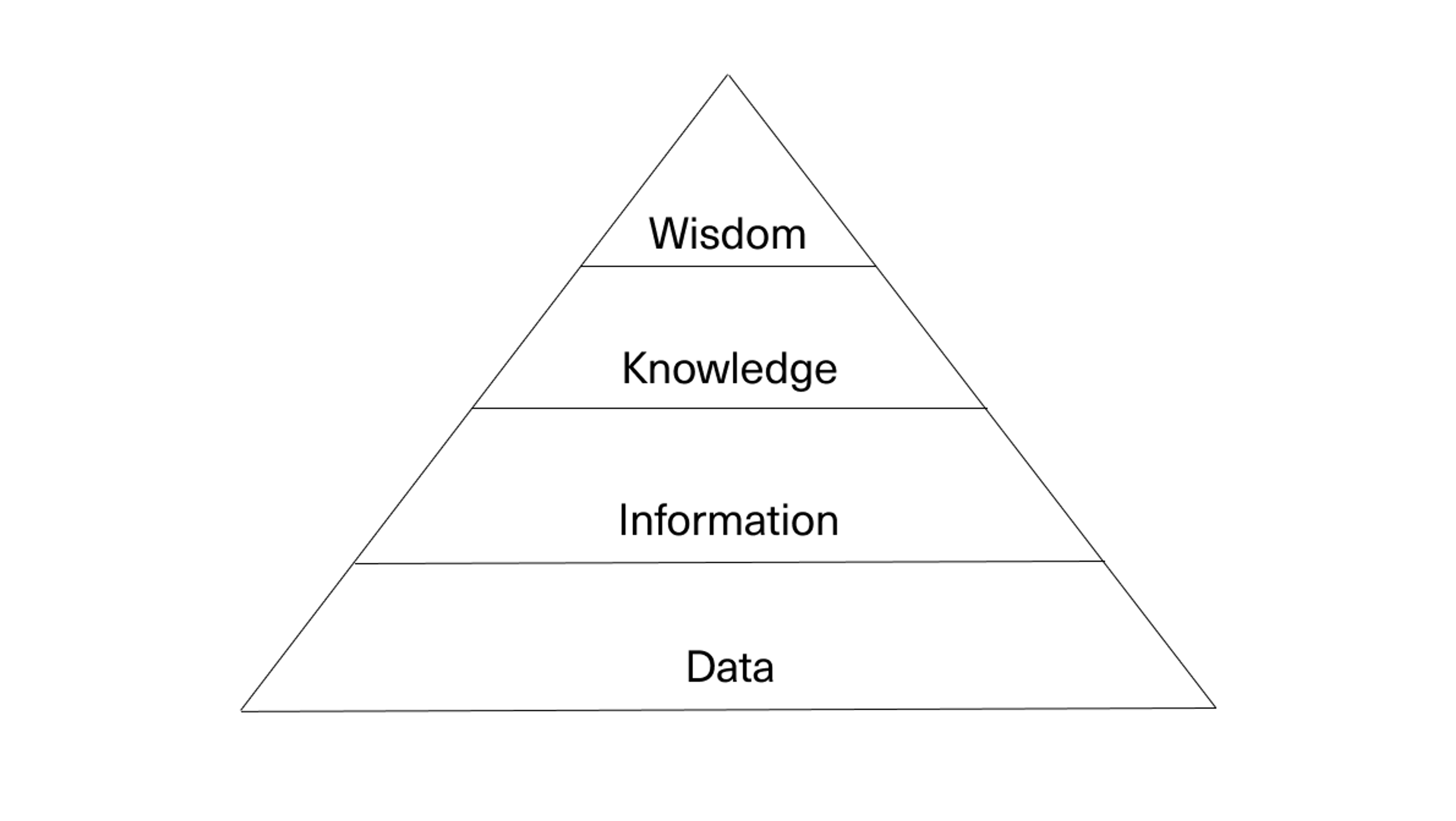

Data is not exactly the same as information or knowledge, even though all these terms are closely linked. Simply put, it’s only when data is interpreted and put in context—i.e., given a meaning or significance—that it becomes information.

In turn, we can lean on data and information to acquire and develop knowledge. Knowledge can again form a basis for wisdom.

You can see this as four levels:

Say, for example, that you want to know whether it is, on average, colder at your place or your friend’s place. First, you need data: readings of each of your thermometers, weather forecasts and statistics for each area. Perhaps you want to compare electricity bills. And your friend telling you that she’s shivering from the cold—that’s data too.

Second, you need to sort this data and put it in context. For example, you can sort thermometer readings from each place over a certain period and draw it up as a graph. This will give you information.

To be sure of the results, the information should be fact-checked and tested. Perhaps there exists other data that can provide the same information, so you can compare and confirm the results. If you have good enough data, you can soon draw a conclusion.

In this example, there is likely a definitive answer. Much of what we want to find out in the real world is a bit more complicated. Knowledge is the result of a persistent search for information and interpretations; it is always in motion. Knowledge is influenced by context, it is complex, and it is only acquired over time, through long-lasting work and experience. It can rely on many different sources of information—which in turn can emerge from large quantities of data.

Data as raw material

Digital technology plays an increasingly significant role in our daily lives, both as individuals, as professionals, and as citizens. We engage with the digital world directly through our phones, tablets or computers, and also indirectly when we are being registered by cameras, sensors and IoT devices.

All of this data is not only interesting in retrospect, for those who want to do high-tech detective work on those digital traces in search of valuable information and knowledge.

Data is also used directly, in real time.

On the one hand, data can be seen as raw information. On the other hand, it can be seen as a raw material that shapes the digital products and services that surround us. Data is fed in real time into the algorithms that control the digital services we use all the time.

Algorithms

Algorithms are something we hear about all the time. But what are they really? Here, you’ll get the answer.